Samuel Johnson? Apocryphal?

Question for Quote Investigator: After Samuel Johnson published his masterful dictionary of the English language he was reportedly approached by two prudish individuals:

“Mr. Johnson, we are glad that you have omitted the indelicate and objectionable words from your new dictionary.”

“What, my dears! Have you been searching for them?”

Recently, I heard a different version of this anecdote in which an interlocutor was unhappy to discover that improper words were present in the new opus:

“I am sorry to see, Dr. Johnson, that there are a few naughty words in your dictionary.”

“So, madam, you have been looking for them?”

Could you explore these contradictory tales?

Reply from Quote Investigator: Samuel Johnson released “A Dictionary of the English Language” in 1755, and the earliest printed evidence of this anecdote known to QI appeared in April 1785. An article titled “Dr. Johnson at Oxford, and Lichfield” in the London periodical “The Gentleman’s Magazine” recounted a meeting between the great linguist and an admirer:1

A literary lady expressing to Dr. J. her approbation of his Dictionary and, in particular, her satisfaction at his not having admitted into it any improper words; “No, Madam,” replied he, “I hope I have not daubed my fingers. I find, however that you have been looking for them.”

In July 1785 the same story was disseminated further when it was reprinted in “The Scots Magazine”.2

Different versions of this tale have been propagated for more than 230 years. In 1829 an instance was published in which two women were named as Johnson’s conversation partners: Mrs. Digby and Mrs. Brooke. They commended the dictionary-maker for omitting naughty words and received the same cleverly acerbic response.

By 1884 a variant anecdote was circulating in which an individual “was sorry to find a few naughty words” in the two-volume lexicon. Johnson’s reply was largely unmodified. The details for these citations are given further below.

Here are additional selected citations in chronological order.

In 1823 an instance of the tale was published in a London magazine called “The Nic-Nac; or, Oracle of Knowledge”:3

To an affected lady, who told him that she highly approved of his not having admitted any improper words into his work, he said, “What, then, I suppose, madam, you have been looking for them.”

In 1825 a periodical in Lexington, Kentucky published the anecdote and referred to Johnson as a “surly sage”:4

“I am glad, sir” said a lady to Dr. Johnson, “that you have omitted all improper words from your dictionary.” “I hope I have, madam,” answered the surly sage, “but I see you have been looking for them.”

In 1825 a compilation of humor titled “The Laughing Philosopher” was published in London. In this retelling of the incident Johnson’s phrase “not daubed my fingers” was changed to “not soiled my fingers”:5

A literary lady expressing to Dr. Johnson her approbation of his Dictionary, and in particular her satisfaction at his not admitting into it any improper words. “No Madam,” replied he “I hope I have not soiled my fingers; I find, however, that you have been looking for them.”

In 1829 “Personal and Literary Memorials” by Henry Digby Beste was released, and the author presented an entertaining yarn that ostensibly identified two women who spoke to Johnson about the omission of taboo words in his masterwork:6

Mrs. Digby told me that when she lived in London with her sister Mrs. Brooke, they were, every now and then, honoured by the visits of Dr. Samuel Johnson. He called on them one day, soon after the publication of his immortal Dictionary. The two ladies paid him due compliments on the occasion. Amongst other topics of praise, they very much commended the omission of all naughty words. “What! my dears! then you have been looking for them?” said the moralist. The ladies, confused at being thus caught, dropped the subject of the dictionary.

Note that the dictionary was published in 1755 and the above account was printed in 1829; hence, the delay measured almost 75 years. Yet, this version of the anecdote has proved popular, and a reviewer in “The Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres” reprinted the text in August 1829.7

In 1870 the compilation “Mirthfulness and Its Exciters; or, Rational Laughter and Its Promoters” included the following passage:8

Two ladies, encountering Dr. Johnson soon after the publication of his “Dictionary,” complimented him for having omitted gross, indelicate, and objectionable words.

“What, my dears!” said the doctor, “have you been searching for them?”

By 1884 a novel variant of the episode had emerged in which Johnson was criticized instead of commended because unsuitable words had been located in his dictionary:9

A Scotch lady of position one evening at a dinner party said to the Doctor that his dictionary was a great work, but that she was sorry to find a few naughty words in it. “Madam,” said Johnson, “I see that you must have been looking for them.”

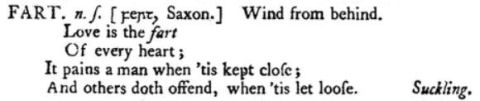

In fact, Samuel Johnson did include words that some readers would consider indelicate such as “fart” defined as “Wind from behind”, and he illustrated the meaning with a quotation from Sir John Suckling:

Love is the fart

Of every heart;

It pains a man when ’tis kept close;

And others doth offend, when ’tis let loose.

Here is a digital reproduction of the entry from the 1755 edition of the dictionary:10

In 1885 “The Enchiridion of Wit: The Best Specimens of English Conversational Wit” printed an instance of the anecdote:11

Self-Convicted.

Soon after the publication of the English Dictionary, a lady said to the author, “I am sorry to see, Dr. Johnson, that there are many naughty words in your dictionary.” “So, madam, you have been looking for them?” was the stunning reply.

In 1906 the New York periodical “The Critic” printed a version of the tale:12

They recalled to mind Dr. Johnson’s reply to the lady who said she was so sorry to see he had put all the wicked and improper words in his dictionary—”And I am sorry to see, Madam, that you have been looking for them.”

In 1934 an article in the journal “American Speech” described a handwritten note inscribed on a second edition of Johnson’s 1755 dictionary. The note presented a version of the anecdote that was very similar to the account in the April 1785 citation given previously. The distinctive phrase “not daubed my fingers” was used. The note was written between 1755 and 1795; hence, the chronological order of events is uncertain. For example, the note may have been copied from the “The Gentleman’s Magazine”. Alternatively, the tale in “The Gentleman’s Magazine” may have been derived from the note:13

Shortly after the Dictionary was published a literary lady complimented him upon it and particularly expressed her satisfaction that he had not admitted any improper words. “No, Madam,” he replied, “I hope I have not daubed my fingers. I find, however, that you have been looking for them.” [Footnote 42]

[Footnote 42] MS note by (Sir) Herbert Croft, a friend of Johnson’s, in the front of his copy of the Dictionary (2nd ed.; 1755), now owned by the writer. … Croft disposed of his copy in 1795 …

In conclusion, this entertaining story has multiple versions. Currently, the earliest known instance appeared in 1785, shortly after the death of Johnson and three decades after the dictionary debuted in 1755. Any anecdote set “soon after the publication” of the dictionary must have been unpublicized for many years, it seems, and a long delay reduces confidence in veracity.

The 1829 tale featuring Mrs. Digby and Mrs. Brooke is intriguing, but it was published quite late, and the account was secondhand.

The version in which Johnson was complimented for omitting words was in circulation for many years before the variant in which Johnson was reproved for including taboo words. QI believes the second archetypal story evolved from the first.

Update History: On January 27, 2025 the format of the bibliographical notes was updated.

- 1785 April, The Gentleman’s Magazine, “Dr. Johnson at Oxford, and Lichfield”, Start Page 288, Quote Page 288, Column 2, Printed by John Nichols for D. Henry, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1785 July, The Scots Magazine, Volume 47, Anecdote, Quote Page 347, Column 1, Printed by Murray and Cochrane, Edinburgh, Scotland. (Google Book full view) link ↩︎

- 1823 August 30, The Nic-Nac; Or, Oracle of Knowledge, Volume 1, Number 40, Johnson’s Dictionary, Start Page 315, Quote Page 316, Column 2, Printed and Published by T. Wallis, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1825 December 28, The Western Luminary, Volume 2, (Issue Start Page 393), Anecdotes, Quote Page 399, Column 2, Lexington, Kentucky. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1825, The Laughing Philosopher: Being the Entire Works of Momus, Jester of Olympus; Democritus, the Merry Philosopher of Greece, Translated by John Bull, Loose Readings, Quote Page 535, Column 2,Published by Sherwood, Jones, and Co, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1829, Personal and Literary Memorials by (Henry Digby Beste), Quote Page 11 and 12, Published by Henry Colburn, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1829 August 22, The Literary Gazette and Journal of Belles Lettres, (Book Review of “Personal and Literary Memorials”, Book Publisher Henry Colburn, London), Quote Page 548, Column 2, Printed by James Moyes, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1870, Mirthfulness and Its Exciters; or, Rational Laughter and Its Promoters by B. F. Clark (Benjamin Franklin Clark), Quote Page 246, Lee and Shepard, Boston, Massachusetts. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1884, Johnson: His Characteristics and Aphorisms by James Hay, Quote Page cxxv (125), Alexander Gardner, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- Website: Johnson’s Dictionary Online, Page View of Page 775, Dictionary Entry: noun “fart”, Website description: “A Dictionary of the English Language. A Digital Edition of the 1755 Classic by Samuel Johnson”. (Accessed johnsonsdictionaryonline.com on September 22, 2013) link ↩︎

- 1885, The Enchiridion of Wit: The Best Specimens of English Conversational Wit, (Edited by William Shepard Walsh), Self-Convicted, Quote Page 107, J. B. Lippincott & Company, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1906 February, The Critic, Volume 48, Number 2, Women and the Unpleasant Novel by Geraldine Bonner, Start Page 172, Quote Page 172, Column 1, Published for The Critic Company by G. P. Putnam’s Sons, New York. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1934 December, American Speech, Volume 9, Number 4, An Obscenity Symbol by Allen Walker Read, (Footnote Start Page 264, Quote Page 271, Published by Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina. (JSTOR) link ↩︎