Abraham Lincoln? Traveler? John Randolph of Roanoke? Apocryphal?

Question for Quote Investigator: According to legend when Abraham Lincoln was served a cup of unpalatable brew he made the following hilarious remark:

If this is coffee, please bring me some tea; but if this is tea, please bring me some coffee.

I have not been able to find a solid citation for this saying. Are these really the words of Old Abe?

Reply from Quote Investigator: The earliest instance of this quip known to QI appeared in January 1840 in the “Madison Courier” of Madison, Indiana. The speaker was an unidentified “distinguished citizen of North Carolina”. Boldface has been added to excerpts:1

It is said, that once, on an occasion when a distinguished citizen of North Carolina, was disgusted by the taste of some beverage or other which was placed before him at a public table to answer the place of coffee or tea, he exclaimed, ‘boy! if this is tea bring me coffee, and if it is coffee bring me tea.’

The same jocular item was disseminated in other newspapers in 1840 such as “The North-Carolina Standard”2 of Raleigh, North Carolina and “The Camden Journal” of South Carolina.3

By 1852 the witticism had been assigned to a Congressman from Virginia with the moniker John Randolph of Roanoke. This ascription became common, but the supporting evidence was weak because Randolph had died many years earlier in 1833.

Special thanks to the fine researcher Barry Popik who located the January 1840 citation and the earliest citation crediting John Randolph. Popik’s webpage on this topic is located here.

By 1902 the remark had been re-assigned to the famous statesman Abraham Lincoln who died in 1865. Nowadays, this unlikely ascription has become prevalent. It is true that the joke was circulating while Lincoln was alive; thus, it was conceivable he employed it; however, QI has found no contemporaneous citations to support this possibility.

This entry presents a snapshot of what is known. The joke was initially linked to an unknown “distinguished citizen of North Carolina”, but the anecdote was prefaced with the locution “it is said” signaling that the tale was being relayed via indirect knowledge. Indeed, the scenario might have been concocted by an anonymous jokesmith. More may be learned by future researchers.

Here are additional selected citations in chronological order.

Another version of this jest was located by QI in multiple U.S. newspapers in June 1840. A political correspondent called “Spy in Washington” relayed remarks made by an unnamed member of Congress. Boldface has been added to excerpts:

The honorable member paused a few moments, and, then replied—”I suspect my people are in the situation of a traveler that I once heard of. He stopped at an inn to breakfast, and having drank a cup of what was given him, the servant asked, what will you have, tea or coffee?” To which the traveler answered—

“That depends upon circumstances. If what you gave me last was tea, I want coffee. If it was coffee, I want tea.—I want a change.”

The politician was presenting a joke that was already in circulation, and the punchline was delivered by an unidentified traveler. The piece above was widely distributed in 1840 and appeared in newspapers such as “The Indiana Journal” of Indianapolis, Indiana,4 “The Adams Sentinel and General Advertiser” of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania,5 and “The Schenectady Cabinet Or, Freedom’s Sentinel” of Schenectady, New York.6

In 1841 “The London Saturday Journal” printed the humorous tale of the anonymous traveler and the mysterious beverage:7

A traveller stopped at an inn to breakfast, and having drunk a cup of what was given him, the servant asked, “What will you have, tea or coffee?” The traveller answered—”That depends upon circumstances. If what you gave me was tea, I want coffee. If it was coffee, I want tea. I want a change.”

In 1844 the editor of a New York monthly called “The Knickerbocker” received a note from a writer who inquired whether he should submit prose or poetry for publication. The editor was very critical of the writer’s previous output and responded with derision. The following passage contained the Latin phrase “medio tutissimus ibis” meaning “you will go most safely by the middle course”:8

We hardly know what to say, in answer to this categorical query. It will not perhaps be amiss, however, to adopt the in medio tutissimus ibis style of the traveller, who, upon calling for a cup of tea at breakfast, handed it back to the servant, after tasting it, with the remark: ‘If this is tea, bring me coffee—if it is coffee, bring me tea; I want a change.’ If what ‘M.’ sends us is poetry, let him send us prose; if it is prose, (and it certainly ‘has that look,’) let him send us poetry, by all means.

In 1846 a Boston, Massachusetts periodical called “The Literary Museum” printed a version of the comical story with a local Boston setting:9

RATHER UNCERTAIN—A gentleman who had lately arrived at a boarding house in this city, demanded of the lady of the establishment, at his first breakfast, whether she had helped him to tea or coffee.”

“What do you mean, sir?–why do you ask?” said the lady.

“Because,” replied the gentleman, “if this is tea give me coffee; and if coffee give me tea.”

In 1852 “Harper’s New Monthly Magazine” of New York published an article titled “John Randolph of Roanoke: Personal Characteristics, Anecdotes, Etc., Etc.” which included an instance of the quip purportedly spoken by Randolph. The setting was a hotel dinner-table in Richmond, Virginia:10

“Take that away—change it.” “What do you want, Mr. Randolph?” asked the waiter, respectfully. “Do you want coffee or tea?”

“If that stuff is tea,” said he, “bring me coffee; if it’s coffee, bring me tea: I want a change!”

The above citation was the first linkage to Randolph known to QI. The length of time between the death of Randolph in 1833 and this publication in 1852 substantially reduced the credibility of the tale.

In 1859 the book “Ten Years of Preacher-Life: Chapters from an Autobiography” by William Henry Milburn referred to the story:11

Our fare at dinner was, of course, the never eaten roast beef, roast pig and sole-leather pudding; and for breakfast and tea, a dark colored witch’s broth, that reminded one of Mr Randolph’s retort upon a waiter, in hearing of the proprietor of a Richmond hotel.

“Boy,” said the beardless lord of Roanoake, “change my cup.” “Will you have coffee or tea, Mr. Randolph?” “If this is coffee, bring me tea; and if this is tea, bring me coffee—I want a change.”

In 1878 a volume based on the reminiscences of old neighbors and acquaintances of Randolph was published. The anecdote was shifted in time from the dinner table to the breakfast table:12

On one occasion he was at breakfast, when a cup was set at his plate. “Servant,” said he, “If this be coffee, give me tea, and if it be tea, give me coffee.”

In February 1902 a journal based in Boston, Massachusetts called “The Advocate of Peace” printed a speech that ascribed the quip to Abraham Lincoln:13

As Mr. Lincoln said, “If this is coffee, give me tea; if it is tea, give me coffee.”

The above citation was the first linkage to Lincoln found by QI. Many sayings have incorrectly been attributed to the popular President who died more than 36 years before the 1902 speech was delivered.

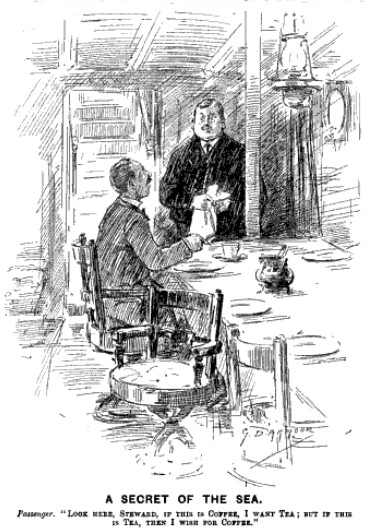

In July 1902 the influential London humor magazine “Punch” printed a one-panel comic with a caption presenting the jest:14

A SECRET OF THE SEA.

Passenger. “Look here, Steward, if this is coffee, I want tea; but if this is tea, then I wish for coffee.”

The poet Carl Sandburg wrote a celebrated six-volume biography of Lincoln, and the second volume released in 1929 included an instance of the joke. Sandburg expressed skepticism about the attribution, and he noted that if “a story or saying had a certain color or smack, it would often be tagged as coming from Lincoln”:15

And of course, said some jokers, it was Abe Lincoln who first told a hotel waiter, “Say, if this is coffee, then please bring me some tea, but if this is tea, please bring me some coffee.”

In 1949 the industrious quotation collector Evan Esar attributed the remark to Lincoln in “The Dictionary of Humorous Quotations”:16

LINCOLN, Abraham, 1809-1865, President of the United States.

If this is coffee, please bring me some tea; but if this is tea, please bring me some coffee.

In 1956 a writer in “The Boston Globe” praised Lincoln for displaying humor instead of anger:17

Lincoln used a jest when other people might show anger. Given something distasteful in a restaurant one day, he called the waiter and said: “If this is coffee, please bring me some tea. But if this is tea, bring me some coffee.”

In conclusion, the quotation first appeared as the punchline of a joke that was circulating by 1840. Within the joke the words were spoken by a “distinguished citizen of North Carolina” or by an anonymous “traveler”. By 1852 John Randolph of Roanoke, Virginia was assigned the role of the traveler and the jest was ascribed to him. By 1902 the punchline was also being credited to the luminary Abraham Lincoln. Both later attributions were unlikely.

Acknowledgement: Great thanks to George Dinwiddie whose inquiry led QI to formulate this question and perform this exploration. Many thanks also to Barry Popik for his valuable research.

Update History: On November 18, 2015, citations dated January 18, 1840; February 12, 1840; and May 2, 1840 were added. The conclusion was partially rewritten. On January 14, 2025 the format of the bibliographical notes was updated.

- 1840 January 18, Madison Courier, (Short untitled item), Quote Page 1, Column 6, Madison, Indiana. (NewspaperArchive) ↩︎

- 1840 February 12, The North-Carolina Standard, (Untitled short item), Quote Page 4, Column 2, Raleigh, North Carolina. (Chronicling America) ↩︎

- 1840 May 2, The Camden Journal, (Untitled short item), Quote Page 1, Column 5, Camden, South Carolina. (Chronicling America) ↩︎

- 1840 June 6, Indiana Journal, (Indianapolis Indiana Journal), Capital, Quote Page 3, Column 2, Indianapolis, Indiana. (NewspaperArchive) ↩︎

- 1840 June 8, The Adams Sentinel and General Advertiser, (Gettysburg Adams Sentinel), (Untitled short article), Quote Page 7, Column 3, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. (NewspaperArchive) ↩︎

- 1840 June 16, The Schenectady Cabinet: Or, Freedom’s Sentinel (Cabinet), Capital, Quote Page 3, Column 2, Schenectady, New York. (GenealogyBank) ↩︎

- 1841 April 24, The London Saturday Journal, Conducted by James Grant, Varieties, Quote Page 204, Published by W. Brittain, Paternoster Row, London. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1844 April, The Knickerbocker Or, New-York Monthly Magazine, Volume 23, Number 4, Editor’s Table, Start Page 389, Quote Page 398, Published by John Allen, Nassau-Street, New York. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1846 April 18, The Literary Museum: An Annual Volume of the Useful and Entertaining, Volume 3, Number 8, Rather Uncertain (short item), Quote Page 58, Published by J. B. Hall and Company, Boston, Massachusetts. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1852 September, Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, John Randolph of Roanoke: Personal Characteristics, Anecdotes, Etc., Etc., Start Page 531, Quote Page 534, Column 1, Harper & Brothers Publishers, New York. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1859, Ten Years of Preacher-Life: Chapters from an Autobiography by William Henry Milburn, Quote Page 192, Derby & Jackson, New York. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1878, Home Reminiscences of John Randolph, of Roanoke by Powhatan Bouldin, Footnote, Quote Page 50, Published by The Author, Danville, Virginia, Printed by Clemmitt & Jones, Richmond, Virginia. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1902 February, The Advocate of Peace, Volume 64, Number 2, Chinese Exclusion by William Lloyd Garrison (This might be the son of the famous William Lloyd Garrison who died in 1879), (From an address before the Henry George Club, Philadelphia, January 12), Start Page 35, Quote Page 37, Column 2, American Peace Society, Boston, Massachusetts. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1902 July 23, Punch, Or the London Charivari, (Caption of one-panel comic), Quote Page 45, Published at The Office of Punch, London. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1926, Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years by Carl Sandburg, Volume 2 of 2, Quote Page 297, Published by Harcourt, Brace & Company, New York. (Verified with scans) ↩︎

- 1949, The Dictionary of Humorous Quotations, Edited by Evan Esar, Section: Abraham Lincoln, Quote Page 130, Doubleday, Garden City, New York. (Verified on paper in 1989 reprint edition from Dorset Press, New York) ↩︎

- 1956 February 12, Daily Boston Globe, Lincoln’s Wit Bubbled Up Despite Sorrow by Jerry Klein, Quote Page C4, Column 6, Boston, Massachusetts. (ProQuest) ↩︎