Oliver Cromwell? John Andrewes? Earl of Chichester? Mark Antony Lower? Viscount Fauconberg? Apocryphal?

Question for Quote Investigator: A popular saying extols continuous improvement. Here are four versions:

- He who ceases to be better ceases to be good.

- He who ceases to improve, ceases to be good.

- If I cease becoming better, I shall soon cease to be good.

- If I am not better I am not good.

This saying has been credited to the controversial English military and political leader Oliver Cromwell. Would you please explore this adage?

Reply from Quote Investigator: This adage was in circulation by 1621 when it appeared in a book titled “A celestiall looking-glasse to behold the beauty of heauen” by John Andrewes. Spelling had not yet been standardized when this book was published. A section called “An Apologie of the Author to the Reader” contained a Latin version of the saying together with an English translation. Boldface added to excerpts by QI:1

Qui cessat esse melior, cessat esse bonus.

Hee that ceasseth to be better, ceasseth to be good

A contemporary formulation of this statement would be:

He that ceases to be better, ceases to be good

In 1630 the Latin expression appeared in a collection titled “Panacea: or, Select Aphorismes, Diuine and Morall”:2

It is not enough to repent, but thou must proceed from grace to grace, if thou wouldst atchieue the Crowne of Glory:

(Nam qui cessat esse melior, cessat esse bonus.)

Oliver Cromwell died in 1658, and the earliest linkage of the saying to the famous leader located by QI appeared almost two centuries later. An article titled “Remarks on the Pocket Bible of Oliver Cromwell with His Autograph” was read at an 1848 meeting of the Sussex Archaeological Society of England, and the article was printed in a volume of the “Sussex Archaeological Collections” in 1849:3

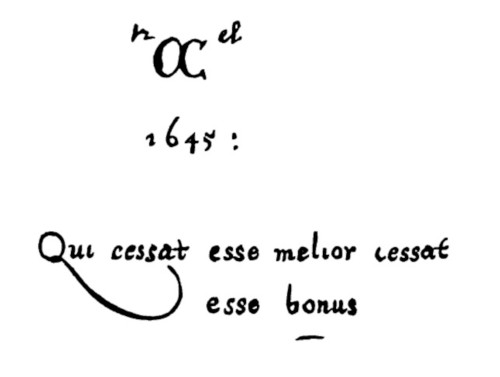

At the Society’s Annual Meeting, held at Lewes, 10th of August, 1848, the Earl of Chichester, one of the vice presidents of the Society, exhibited the Pocket Bible of Oliver Cromwell. It is the edition of 1645, “printed for the assignes of Robert Barker,” and is plainly bound, for portability, in four thin volumes. The autograph of the original proprietor is written at the beginning of the third volume only:

The Earl of Chichester believed that the large O and C were the authentic signature of Oliver Cromwell. The Latin statement accompanying the signature can be translated in several different ways. Here is another possible rendering:

Qui cessat esse melior cessat esse bonus

He who ceases to improve, ceases to be good

Below are additional selected citations in chronological order.

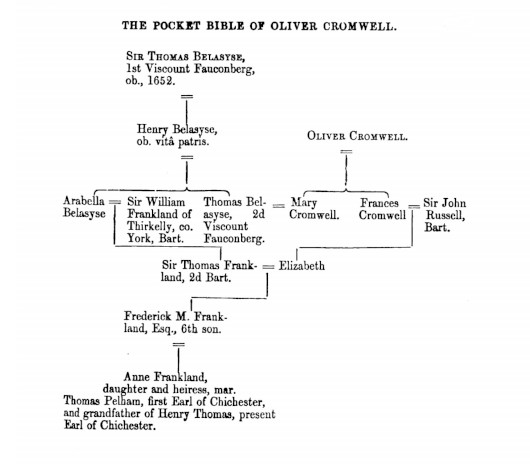

The article about the Earl of Chichester’s 1848 exhibit was written by Mark Antony Lower. The article mentioned that the autograph of the second Viscount Fauconberg was present in all the volumes of the bible as: ‘Lord ffauconberg, his booke, 1677.’

A genealogical chart accompanying the article helped to explain how the Earl of Chichester became the current owner of the bible. Cromwell’s granddaughter was the Earl of Chichester’s great-great grandmother.

In 1849 “The Gentleman’s Magazine” printed an article discussing the artifact and repeated the information in the piece by Mark Antony Lower.4

In 1857 “The Journal of the British Archaeological Association” printed a piece titled “On Cromwellian Relics”. In the following excerpt “protector” refers to Oliver Cromwell who served in a position called Lord Protector:5

A far more curious and undoubted relic of the protector is his pocket Bible, now in the possession of the earl of Chichester, who is a descendant, in an indirect line, from Cromwell.

The article largely repeated the information in the previous pieces on this topic and included the Latin adage:

Qui cessat esse melior, cessat esse bonus.

In 1883 “The Saturday Review” of London described some of the items displayed at the Museum in the County Hall at Lewes, England. Boldface added to excerpts by QI:6

In an inner chamber were some rubbings of brasses, a set of the facsimiles of the Bayeux tapestry, and some early printed books in a case which also contained the four volumes of Cromwell’s pocket Bible, lent by Lord Chichester. It was a copy of the large 12mo, edition of 1645, itself very rare if, not unique, printed by the “Assignes of Robert Barker,” who died that very year in prison. On one of the fly-leaves was written very neatly, “Oer. Cel. 1645: Qui cessat esse melior cessat esse bonus.” Above was written, “Lord ffauconberg, his Booke, 1677.”

In 1886 “Walford’s Antiquarian: A Magazine and Bibliographical Review” discussed the adage and presented a translation into English:7

“That is, in plain English, ‘He who ceases to be better ceases to be good.’ And if that be not a good lesson for everyone of us, even the most consistent Christian, I do not know one.”

The edition of the Bible, it may be remarked, is that of 1645, the same date as that of Cromwell’s inscription.

In 1899 a religious text titled “Christ in Creation and Ethical Monism” by Professor of Biblical Theology Augustus Hopkins Strong presented the saying in Latin and English:8

The Christian pastor who neglects his own spiritual life in order to minister to others will soon find that he has nothing to give. In an old Bible belonging to Oliver Cromwell was found this inscription: “O. C., 1644—Qui cessat esse melior cessat esse bonus”—”He who ceases to be better ceases to be good.”

In April 1905 “The Washington Post” stated that the new Lord Chichester was a soldier. The newspaper described the pocket bible and its inscription:9

And at Stanmer Park, the ancestral home of the head of the historic House of Pelham, Lord Chichester has among his treasures Cromwell’s pocket Bible, with a motto “Qui cessat esse melior, cessat esse bonus,” (He who ceases to improve, ceases to be good), in the great Lord Protector’s own handwriting.

In October 1905 “The Conneautville Courier” of Pennsylvania printed yet another possible translation of the Latin motto. The paper left readers with the impression that the original inscription was in English:10

It is said that in Cromwell’s Bible it was written, “If I cease becoming better, I shall soon cease to be good.”

In 1910 “The New York Observer” attributed a cogent remark to the prominent Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen. The journal also attributed another English version of the saying under analysis to Cromwell:11

And no advancement can be made in the spiritual life without our determining that we shall advance. When Thorwaldsen was asked, “Which is your greatest statue?” he replied, “The next one.” “If I cease to become better,” Cromwell is said to have written in his Bible, “I shall cease to be good.” Even the best may be bettered. Indeed, it must be bettered if it is not to grow worse. We are meant to advance always upon our past.

In 1918 “Church Year Sermons for Children” printed another English instance of the saying:12

Let us always remind ourselves: “HE WHO STOPS BEING BETTER, STOPS BEING GOOD,” and “WHEN I HAVE DONE A GOOD THING THEN I MUST DO STILL BETTER.”

In conclusion, this saying appeared in Latin and English in 1621 within a book by John Andrewes; however, the saying was not integrated into the main text. It was freestanding which signaled that it was not crafted by Andrewes; instead, the adage was already in circulation.

There is substantive evidence that Oliver Cromwell wrote the Latin adage “Qui cessat esse melior cessat esse bonus” in his pocket bible. The published evidence does not provide certainty because there was a long delay from the death of Cromwell in 1658 to the reported exhibition of the pocket bible containing the Latin inscription which occurred in 1848 according to the article in the “Sussex Archaeological Collections”.

QI does not know whether knowledgeable experts have examined the pocket bible which is probably available in a museum or a private collection today. Future researchers may be able to share forensic data about that artifact. In addition, future researchers may find written evidence of a linkage before 1848.

Image Notes: Illustration of a graph showing lines heading downward and upward from Mediamodifier at Pixabay.

Acknowledgement: Great thanks to Gerald Krieghofer whose inquiry led QI to formulate this question and perform this exploration. Special thanks to Stephen Goranson who accessed scans of the 1630 citation.

Update History: On April 3, 2025 the format of the bibliographical notes was updated.

- 1621, Title: A celestiall looking-glasse to behold the beauty of heauen. Directed vnto all the elect children of God, very briefly composed, and authentically penned, that it may be effectually gained, Author: John Andrewes, Publisher: Printed by Nicholas Okes, London. (Early English Books Online) link ↩︎

- 1630, Title: Panacea: or, Select Aphorismes, Diuine and Morall, Item Number: 197, Publisher: Printed by Augustine Mathewes, London. (Early English Books Online 2) link ↩︎

- 1849, Sussex Archaeological Collections: Illustrating the History and Antiquities of the County, Volume 2, Article: Remarks on the Pocket Bible of Oliver Cromwell with His Autograph, Location: Read at a Quarterly Meeting at Lewes, Date: October 1848, Author: Mark Antony Lower, Start Page 78, Quote Page 78, Publisher: The Sussex Archaeological Society, Sussex, England; John Russell Smith, London. (HathiTrust Full View) link ↩︎

- 1849 February, The Gentleman’s Magazine, Antiquarian Researches: Sussex Archaeological Society, Start Page 187, Quote Page 187, John Bowyer Nichols and Son, London. (HathiTrust Full View) link ↩︎

- 1857 December, The Journal of the British Archaeological Association, Volume 13, “On Cromwellian Relics”, Start Page 341, Quote Page 344, J. R. Smith, London. (HathiTrust Full View) link ↩︎

- 1883 August 11, The Saturday Review, Volume 56, The Archaeological Institute at Lewes, Start Page 174, Quote Page 175, Published at The Office of The Saturday Review, London. (HathiTrust Full View) link ↩︎

- 1886, Walford’s Antiquarian: A Magazine and Bibliographical Review, Edited by Edward Walford (Formerly Scholar of Balliol College, Oxford, and late Editor of “The Gentleman’s Magazine”), Volume 9, Start Page 111, Quote Page 113, George Redway, London. (HathiTrust Full View) link ↩︎

- 1899, Christ in Creation and Ethical Monism by Augustus Hopkins Strong (Professor of Biblical Theology in the Rochester Theological Seminary), Addresses to Successive Graduating Classes of the Rochester Theological Seminary: Persistence, Start Page 496, Quote Page 499, The Roger Williams Press, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (HathiTrust Full View) link ↩︎

- 1905 April 29, The Washington Post, News and Gossip of Foreign Lands, Quote Page 6, Column 5, Washington D.C. (Newspapers_com) ↩︎

- 1905 October 11, The Conneautville Courier, Christian Endeavor of the Presbyterian Church, Edited by the C. E. Society, Quote Page 3, Column 6, Conneautville, Pennsylvania. (Newspapers_com) ↩︎

- 1910 December 29, The New York Observer, Resolutions for the New Year: Commending the Old-Fashioned Practice–A Creed of Hope by the Rev. G. B. F. Hallock, Start Page 833, Quote Page 833 and 834, The New York Observer Company, New York. (HathiTrust) link ↩︎

- 1918 (Copyright 1917), Church Year Sermons for Children by Phillips E. Osgood, The Whistle With a Steamboat Start Page 207, Quote Page 209, George W. Jacobs & Company, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (HathiTrust Full View) link ↩︎