Samuel Johnson? Martin Sherlock? Johann Heinrich Voss? Gotthold Ephraim Lessing? Richard Brinsley Sheridan? Daniel Webster? Samuel Wilberforce

Question for Quote Investigator: The great lexicographer Dr. Samuel Johnson is credited with a famously devastating remark about a book he was evaluating:

Your manuscript is both good and original; but the part that is good is not original, and the part that is original is not good.

I have never found a source for this quotation in the writings of Johnson, and I have become skeptical about this attribution. Do you know if he wrote this?

Reply from Quote Investigator: No substantive evidence has emerged to support the ascription to Samuel Johnson. In this article QI will trace the evolution of this saying and closely related expressions which have been attributed to a variety of prominent individuals. The following four statements have distinct meanings, but they can be clustered together semantically and syntactically.

- What is new is not good; and what is good is not new.

- What is new is not true; and what is true is not new.

- What is original is not good; what is good is not original.

- What is new is not valuable; what is valuable is not new.

The earliest evidence known to QI of a member of this cluster appeared in 1781 and was written by Reverend Martin Sherlock who was reviewing a popular collection of didactic letters published in book form. Lord Chesterfield composed the letters and sent them to his son with the goal of teaching him to become a man of the world and a gentleman. Sherlock was highly critical:1

His principles of politeness are unexceptionable; and ought to be adopted by all young men of fashion; but they are known to every child in France; and are almost all translated from French books. In general, throughout the work, what is new is not good; and what is good is not new.

This expression was similar to the one attributed to Samuel Johnson. The word “new” was used instead of “original”. Yet, this passage did not include the humorous prefatory phrase which would have labeled the work “both new and good” before deflating it.

In the 1790s a German version of the saying using “new” and “true” was published in a collection by the translator and poet Johann Heinrich Voss. This instance did include a prefatory phrase stating that the “book teaches many things new and true”:2

Dein redseliges Buch lehrt mancherlei Neues und Wahres,

Wäre das Wahre nur neu, wäre das Neue nur wahr!

Here is an English translation:3

Your garrulous book teaches many things new and true,

If only the true were new, if only the new were true!

In 1800 a reviewer in “The British Critic” lambasted a book using a version of the brickbat with “new” and “good”:4

In this part there are some good and some new things; but the good are not new, and the new are not good. Much time is employed in considering the opinion of the poet du Belloy, at present forgotten and of little consequence, who professed to prefer the French to the ancient languages.

Here are additional selected citations in chronological order.

In 1801 some New England newspapers presented an instance of the expression in a section called “London Paragraphs”, i.e., short items from London.5 The words were attributed to Lessing, i.e., the German intellectual Gotthold Ephraim Lessing who died in 1781:6

Nicholai was praising Voltaire for having written so much that is new, and so much that is good. His good is not new—his new is not good, replied Lessing.

In 1806 a harsh review written under the pseudonym The Reasoner was published in “The European Magazine”. The Reasoner attacked the poem “The Progress of Poetry” also known as “The Progress of Poesy” by Thomas Gray.7

With respect to the Progress of Poetry, it will be sufficient to say, that what is good, is not new, and what is new, is not good. Gray has done what every man of tolerable abilities might do; he has copied the principal ideas of his poem from other poets, and has connected and embellished them by his own industry; but whether he imitates others, or relies upon himself alone, he soars into obscurity.

In 1807 a defender of Thomas Gray’s works replied to The Reasoner and accused him of using a borrowed phrase during his disparagement of Gray. A version of the barbed saying using “good” and “new” was attributed to Samuel Johnson, and this was the earliest linkage to Johnson known to QI:8

. . . it would have been but candid if the Reasoner had marked that happy play upon words where he notices the Progress of Poetry, that “What is good is not new, and what is new is not good,” as quotation, as well as marking it in italics; for such it is, I aver, having met with it before, although I cannot at this instant remember where; but to the best of that remembrance, Dr. Johnson makes use of it, and I also think it is in one of his Lives of the Poets.

The popular modern attribution to Johnson is based on the expression using “good” and “original”. Indeed, different variants of the saying are sometimes confused. The passage above is more than two hundred years old; hence, the connection has a long history.

The words of Martin Sherlock were not forgotten and in 1814 he was credited with the gibe using “good” and “new”:9

Such a judgment as Sherlock the Traveller passes on Lord Chesterfield’s Letters, in the Courts below, is enough to terrify a Writer from giving his name to a Reader. This Censurer pronounces of these patrician performances, that ‘what in them is new, is not good; and what is good, is not new.’

In 1821 the playwright and politician Richard Brinsley Sheridan was credited with an instance of the expression using “new” and “true”. Sheridan’s death occurred several years earlier in 1816:10

Sheridan once said of some speech in his acute, sarcastic way, that “it contained a great deal both of what was new and what was true: but that unfortunately what was new was not true, and what was true was not new.”

In 1823 a book reviewer assailed a volume titled “December Tales” using the critical statement with “good” and “original”. This is the first instance using “original” known to QI, but the following passage indicated it was already in circulation:11

Many strong symptoms of book-making are betrayed in this little volume; in which, to borrow a happy antithesis, what is original is not good, and what is good is not original. The tales possess little incident and less interest, and this fault is not compensated by the sentiment, which is rarely simple and real.

In 1829 the Encyclopaedia Americana illustrated the term “Antithesis” by employing an instance of the saying with “good” and “new”. The words were credited to Lessing:12

Antithesis (opposition); a figure of speech, by which two things are attempted to be made more striking, by being set in opposition to each other. This figure often produces a great effect, yet, by too frequent use, becomes disgusting. Lessing affords an instance of a happy antithesis, when, in the review of a book, he says, “This book contains much that is good, and much that is new; only it is a pity that the good is not new, and the new is not good.” Some use antithesis only to express the connexion of things exactly opposite.

In 1836 the ascription to Sherlock was mentioned again in a short note with the heading “Elegant Criticism”:13

Sherlock, the traveller, says of Lord Chesterfield’s Letters, “what in them is new, is not good; and what is good, is not new.”

In 1842 the periodical “The New World: A Weekly Family Journal” printed the expression with “good” and “original” as an anonymous joke:14

What do you think of the music in Horn’s new Opera?” said one to another. “Why,” replied the other, “I think that what is good is not original, and what is original is not good.”

In 1848 the prominent politician and orator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts employed the saying in a major speech. He described a political platform using “new” and “valuable”:15

I speak without disrespect of the Free Soil party. I have read their platform, and though I think there are some rotten places in it, I can stand on it pretty well. But I see nothing in it which is new and valuable; what is valuable is old; and what is new, is not valuable. (Cheers and laughter.)

In 1849 the Transylvania Medical Journal published an instance of the family using “new” and “valuable”:16

Although his book is one of extraordinary pretension, we might have given our opinion of its matter in a single word, “what is new is not valuable, and what is valuable is not new.”

In 1851 the witticism employing “good” and “original” was credited to a “really great writer”:17

And indeed, as a really great writer for the stage once remarked on a similar production—whatever is good is not original, and whatever is original is not good.”

In 1854 a short anecdote about Samuel Johnson and a hopeful author was published. This tale was similar to the modern incarnation, but the expression included “good” and “new”:18

As Dr. Samuel Johnson is said to have remarked to an aspirant to authorship, (who had, in hope of a high recommendation, submitted his manuscript to him,) “Young man, what is new in your production is not good, and what is good is not new,” so similar is the case here.

In 1865 the linkage to Sheridan was mentioned again. In this case, Sheridan’s jest was reportedly aimed at a book instead of a speech and used the words “good” and “original”:19

He spoke of the platform of that party, saying it was open to no criticism, but at the same time quoting Sheridan’s criticism of a book: “There are parts in it both original and good—but what is good is not original, and what is original is not good.”

In 1890 an instance of the expression was assigned to Samuel Wilberforce who was referred to with the moniker Soapy Sam:20

In fact, generally, M. Brunetiere’s criticisms upon his great countryman may be summed up in Soapy Sam’s witticism, That his works contain much that is good and much that is original, but what is original is not good, and what is good is not original.

By 1892 the 1854 tale with Samuel Johnson had evolved. Now the critical expression included the words “good” and “original”:21

Once upon a time, it is said, the great Dr. Johnson returned the manuscript of a youth who aspired to literary renown, with the pointed indorsement: “I find much in this that is good, and much that is new; but that which is good is not new, and that which is new is not good.”

In conclusion, this protean saying is difficult to trace. QI has attempted to assemble a natural grouping of related expressions. Within this grouping the earliest instance was provided by Martin Sherlock in 1781. This citation is solid, but it is possible that it can be antedated. This article presents a snapshot of what is known to QI.

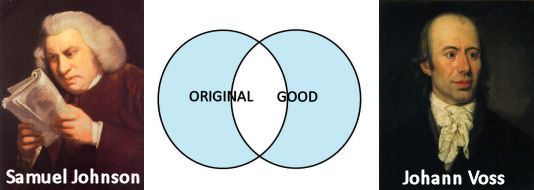

Johann Heinrich Voss and Daniel Webster both used variants of the saying. The ascription to Samuel Johnson is currently unsupported, and may have been introduced via a faulty memory as suggested by the citation in 1807.

Image Notes: Portrait of Samuel Johnson circa 1775 by Joshua Reynolds. Venn diagram created by QI. Portrait of Johann Heinrich Voss circa 1797 by Georg Friedrich Adolph Schöner. Portraits accessed via Wikimedia Commons.

Update History: On September 16, 2024 the format of the bibliographical notes was updated.

- 1781, Letters on Several Subjects by The Rev. Martin Sherlock (Chaplain to the Right Honourable The Earl of Bristol), Volume 2, Letter XIV, Start Page 123, Quote Page 128 and 129, Printed for J. Nichols, T. Cadell, P. Elmsly, H. Payne and N. Conant, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1796, Gedichte, Johann Heinrich Voss, Volume 2, Section: Epigramme (Epigrams), (Standalone short saying titled “XVI: An mehrere Bücher” (16: Of several Books)), Quote Page 281, Frankfurt und Leipzig. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 2006, Brewer’s Famous Quotations, Edited by Nigel Rees, Section Harold MacMillan, Quote Page 305 and 306, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London. (Verified on paper) (This reference gives the following citation for the J. H. Voss quotation: Vossischer Musenalmanach (1792; some references give a date of 1772 which appears to be inaccurate) ↩︎

- 1800 June, The British Critic, Foreign Catalogue: France, Article 56: (Review of Book: Lycée, ou, Cours de littérature ancienne et moderne, Book Author: J. F. Laharpe (Jean-Francois de La Harp)), Start Page 695, Quote Page 696, Printed for F. and C. Rivington, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1801 December 15, Salem Gazette, London Paragraphs, Quote Page 2, Column 3, Salem, Massachusetts. (GenealogyBank) ↩︎

- 1801 December 29, New-Hampshire Gazette, London Paragraphs, Quote Page 2, Column 4, Portsmouth, New Hampshire. (GenealogyBank) ↩︎

- 1806 December, The European Magazine, and London Review, By the Philological Society of London, Volume 50, The Reasoner: No. III, Quote Page 452, Column 2, Published for James Asperne, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1807 February, The European Magazine, and London Review, Volume 51, Letter to the Editor of European Magazine, (Letter dated January 14, 1807): Defence of Gray against the Reasoner’s Second Attack on his Poems by Vindicator, Start Page 106, Quote Page 107, Column 1, Published for James Asperne, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1814, Literary Anecdotes of the Eighteenth Century: Comprizing Biographical Memoirs of William Boywer, Printer, F.S.A. and Many of His Learned Friends, By John Nichols, Volume 8, Quote Page 124, Printed for John Nichols, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1821, Table-talk: Or Original Essays by William Hazlitt, Eassy XV: On Paradox and Common-Place, Start Page 349, Quote Page 349, John Warren, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1823 August, Monthly Review, Monthly Catalogue: Miscellaneous: (Review of December Tales), Quote Page 442, Printed by A. and R. Spottiswoode, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1829, Encyclopaedia Americana: A Popular Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature, History, Politics and Biography, Brought Down to the Present Time; Edited by Francis Lieber, Assisted by Edward Wigglesworth, Volume 1, Quote Page 284, Carey, Lea & Carey, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1836 August 6, The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, Volume 28, Number 790, Pope and Addison, and Their Contemporaries, Quote Page 84, Printed and Published by J. Limbird, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1842 June 4, The New World: A Weekly Family Journal of Popular Literature, Science, Art and News Volume 4, Issue 23, (Freestanding short item), Page 367, Column 3, New York. (ProQuest American Periodicals) ↩︎

- 1848 September 4, The Boston Daily Atlas (Daily Atlas), Speech of Hon. Daniel Webster at Marshfield on September 1, 1848 (Reported for the Atlas), Quote Page 1, Column 7, Boston, Massachusetts. (GenealogyBank) ↩︎

- 1849 June, Transylvania Medical Journal, Volume 1, Number 1, Edited by Ethelbert L. Dudley, (Book Review by W.S.C. of: A Theoretical and Practical Treatise on Human Parturition By H. Miller M.D.), Start Page 64, Quote Page 91, Under the Supervision of the Transylvania Faculty of Medicine, Lexington, Kentucky. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1851, The Gold-Worshippers: Or, The Days We Live In, By the author of “Whitefriars” (Emma Robinson), Volume 2 of 3, Quote Page 115, Parry & Co., London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1854, The Philosophie of Sectarianism: Or a Classified View of the Christian Sects in the United States by Rev. Alexander Blaikie, Quote Page 168, Sampson Low, Son and Company, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1865 October 15, New Orleans Times, Mass Meeting of the National Democratic Party, Quote Page 2, Column 2, New Orleans, Louisiana. (GenealogyBank) ↩︎

- 1890 June, The Review of Reviews, Volume 1, Number 6, The French Reviews: The Revue Des Deux Mondes, Page 525, Column 2, The Review of Reviews, London. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎

- 1892 December, The International Annual of Anthony’s Photographic Bulletin, Glittering Generalities by John W. Alexander of Yonkers, New York, Quote Page 130, E.& H.T. Anthony & Co. Publishers, New York. (Google Books full view) link ↩︎