Hester Lynch Piozzi? William James? Bertrand Russell? Mark Twain? Henry David Thoreau? Carl Sagan? Terry Pratchett? Samuel Purchas? John Locke? George B. Cheever? Joseph F. Berg? George Chainey? John Phoenix? Anonymous?

Question for Quote Investigator: According to legend a prominent scientist once presented a lecture on cosmology which discussed the solar system and galaxies. Afterwards, a critical audience member approached and stated that the information given was completely wrong.

Instead, the world was supported by four great elephants, and the elephants stood on the back of an enormous turtle. The scientist inquired what the turtle stood upon. Another more massive turtle was the reply. The scientist asked about the support of the last turtle and elicited this response:

“Oh, it’s turtles all the way down.”

Some versions of this anecdote use tortoises instead of turtles. A variety of individuals have been linked to this tale including writer Hester Lynch Piozzi, psychologist William James, logician Bertrand Russell, humorist Mark Twain, transcendentalist Henry David Thoreau, astronomer Carl Sagan, and fantasy author Terry Pratchett. Would you please explore this topic?

Reply from Quote Investigator: This anecdote evolved over time. It began with European interpretations of Hindu cosmography. Early instances featuring tortoises and elephants did not mention an infinite iteration; instead, the lowest creature was sitting upon something unknown or on nothing. In 1838 a humorous version employed the punchline “there’s rocks all the way down!” In 1854 a debater used the phrase “there are tortoises all the way down.” By 1886 another punchline was circulating: “it is turtle all the way down!” Here is an overview sampling showing pertinent statements with dates:

1626: the Elephants feete stood on Tortoises, and they were borne by they know not what.

1690: what gave support to the broad-back’d Tortoise, replied, something, he knew not what.

1804: And on what does the tortoise stand? I cannot tell.

1826: tortoise rests on mud, the mud on water, and the water on air!

1836: what does the tortoise rest on? Nothing!

1838: there’s rocks all the way down!

1842: extremely anxious to know what it is that the tortoise stands upon.

1844: after the tortoise is chaotic mud.

1852: had nothing to put under the tortoise.

1854: there are tortoises all the way down.

1867: elephants . . . their legs “reach all the way down.”

1882: the snake reaching all the way down.

1886: it is turtle all the way down!

1904: a big turtle whose legs reach all the way down!

1917: there are turtles all the way down

1927: he was tired of metaphysics and wanted to change the subject.

1967: It’s no use, Mr. James — it’s turtles all the way down.

Below are selected citations in chronological order.

In 1599 religious figure Emmanuelis de Veiga composed a letter in Latin mentioning the cosmological beliefs that he had encountered in Asia. The letter was published in 1601:1

Alii dicebant, terram nouem constare angulis, quibus cælo innititur. Alius ab his dissentiens, volebat terram septem elephantis fulciri; elephantes vero ne subsiderent, super testudine pedes fixos habere. Quærenti quis testudinis corpus firmaret, ne dilaberetur, respondere nesciuit.

In 1626 “Purchas His Pilgrimage, Or Relations of the World and the Religions” by Samuel Purchas included a passage in English reflecting the contents of the 1599 letter. The following excerpt contained non-standardized spelling, e.g., “vp” for “up”, “Heauen” for “Heaven”, and “seuen” for “seven”. Boldface added to excerpts:2

. . . the Earth had nine corners, whereby it was borne vp by the Heauen. Others dissented, and said, that the Earth was borne vp by seuen Elephants; the Elephants feete stood on Tortoises, and they were borne by they know not what.

In 1690 English philosopher John Locke published “An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding” which mentioned this topic:3

And if he were demanded, what is it, that that Solidity and Extension inhere in, he would not be in a much better case, than the Indian before mentioned; who saying that the World was supported by a great Elephant, was asked, what the Elephant rested on; to which his answer was, A great Tortoise: But being again pressed to know what gave support to the broad-back’d Tortoise, replied, something, he knew not what.

In 1804 English writer Hester Lynch Piozzi published “British Synonymy; Or, An Attempt At Regulating the Choice of Words in Familiar Conversation”, and she mentioned this topic:4

. . . the world is set firm upon an elephant’s back. And on what does the elephant stand? Why, on a tortoise. And on what does the tortoise stand? I cannot tell. Such reasoners as these, though perhaps less deep than candid, are better than some of our modern philosophers . . .

In 1826 “The Asiatic Journal” printed an article with a crocodile in the stack. The bottom featured water suspended on air:5

The whole of the Sakwalla, or universe, rests on the back of a huge elephant; the elephant is supported by a crocodile; the crocodile by a tortoise; the tortoise rests on mud, the mud on water, and the water on air!

In 1836 a newspaper in Richmond, Virginia printed a version in which the stack stood on nothing:6

The Earth stands (according to the Indian Phylosophy) on the back of an Elephant—and the Elephant on the back of a tortoise—and what does the tortoise rest on? Nothing!

In August 1838 “The New-Yorker” journal printed a joke with a punchline based on an infinite iteration of rocks. The current magazine “The New Yorker” founded in 1925 is a different publication:7

“The world, marm,” said I, anxious to display my acquired knowledge, “is not exactly round, but resembles in shape a flattened orange; and it turns on its axis once in twenty-four hours.”

“Well, I don’t know any thing about its axes,” replied she, “but I know it don’t turn round, for if it did we’d be all tumbled off; and as to its being round, any one can see it’s a square piece of ground, standing on a rock.”

“Standing on a rock!—but upon what does that stand?”

“Why, on another, to be sure.”

“But what supports the last?”

“Lauk! child, how stupid you are!—there’s rocks all the way down!”

This popular comical anecdote appeared in a variety of periodicals during the following months and years. The phrasing and punctuation varied. In September 1838 “The New-York Mirror” published a version with the exclamation “Lud” instead of “Lauk”:8

“But what supports the last?”

“Lud! child, how stupid you are! There’s rocks all the way down!”

In 1842 an article in “The London University Magazine” stated that the cosmographical question caused anxiety:9

We entirely believe to take up the old fable, that the world rests on the back of the elephant; and we have no manner of doubt that the elephant brings all his sixteen toes to bear upon the back of the tortoise. But, about the tortoise itself, we hear nothing, and we really are extremely anxious to know what it is that the tortoise stands upon.

In 1844 a piece by Reverend George B. Cheever included a rhinoceros in the stack. The bottom featured chaotic mud:10

Besides our nursery rhymes, we are reminded by this powerful process of logic, of the ratiocination of the Indians in regard to the Cosmogony, that the world rests on the back of an elephant, the elephant stands on a great rhinoceros, the rhinoceros on a huge tortoise, and after the tortoise is chaotic mud.

In 1845 an article in “The Yale Literary Magazine” presented a brief instance of the joke with the iterated rocks punchline:11

The most popular theory is, that, wherever in space you find any solid body, it rests on the backs of four huge elephants; these stand likewise upon four tortoises; the tortoises rest on large rocks; and as for the rest of the matter, the general opinion is, that it is ‘rocks all the way down.’ All we can say of this view of the subject, is the same that some other geologists say of their curious theories: “it does not contradict the Mosaic account.”

An entry dated May 4, 1852 in Henry David Thoreau’s notebook referred to the topic:12

No man stands on truth. They are merely banded together as usual, one leaning on another and all together on nothing; as the Hindoos made the world rest on an elephant, and the elephant on a tortoise, and had nothing to put under the tortoise.

A multi-day debate over the veracity of the Bible was held in 1854 between Reverend Joseph F. Berg and Joseph Barker. Berg attempted to ridicule Barker by using a punchline with infinitely iterated tortoises:13

My opponent reminds me of the heathen, who, being asked on what the world stood, replied “On a tortoise.” But on what does the tortoise stand? “On another tortoise.” With Mr. Barker, too, there are tortoises all the way down. (Vehement and vociferous applause.)

In 1867 “The North American Review” of Boston, Massachusetts printed an instance featuring elephants with infinitely long legs:14

They remind us not a little of the demiurges whom the Indian cosmogony reverently interposes between the awful Supreme Being and his humble human offspring; or of the animals which the cosmology of the same Indians sets, one after another, beneath the earth, before arriving finally at the elephants, which need no further supporters, because their legs “reach all the way down.”

In 1882 a published lecture by George Chainey mentioned a stack of animals with a very long snake at the bottom:15

The Hindu mythology represents the world as resting on the back of an elephant, the elephant standing on the back of a turtle, the turtle on the head of a snake, and the snake reaching all the way down. That snake must have a very long tail.

In July 1882 philosopher William James published an essay in “The Princeton Review”, and he mentioned iterated rocks not iterated turtles:16

Like the old woman in the story who described the world as resting on a rock, and then explained that rock to be supported by another rock, and finally when pushed with questions said it was “rocks all the way down,” he who believes this to be a radically moral universe must hold the moral order to rest either on an absolute and ultimate should or on a series of shoulds “all the way down.”

In 1886 Dean Clarke published an article in “Facts” magazine, and he referred to a stack of animals with “turtle” instead of “tortoise”. The punchline used the singular form of “turtle”:17

They said the earth rests upon the back of an elephant, the elephant upon a turtle, and when asked what the turtle rests upon, a “Christian Scientist” among them replied: “Oh, it is turtle all the way down!”

In 1888 Mark Twain published a compilation of short humorous pieces under the title “Mark Twain’s Library of Humor”. A work called “Lectures On Astronomy” by John Phoenix contained the following:18

Up to the time of a gentleman named Copernicus, who flourished about the middle of the Fifteenth Century, it was supposed by our stupid ancestors that the Earth was the centre of all creation, being a large flat body, resting on a rock which rested on another rock, and so on “all the way down,” and that the Sun, planets and immovable stars all revolved about it once in twenty-four hours.

In 1904 “How to Know the Starry Heavens” by Edward Irving presented a turtle with infinitely long legs:19

Many of them have also heard that the stars are far-off suns, floating in practically empty space. Yet not one person in a thousand truly realises what these statements mean. They are merely hearsay, accepted in childlike faith, as some of the ancients accepted the statement that the Earth is supported by a number of elephants standing on the back of a big turtle whose legs reach all the way down!

In 1917 an editorial in a Paterson, New Jersey newspaper used a punchline with the plural form “turtles”:20

They are very much like the old woman who believed that this earth is just like a big pancake and that it rested on the back of a turtle. “And what does that turtle rest upon?” was the query. “Why, bless your dear heart, there are turtles all the way down,” was the reply.

In 1927 Nobel laureate Bertrand Russell referred to the stack of animals:21

Everyone knows about the Hindu who thought that the world does not fall because it is supported by an elephant, and the elephant does not fall because It is supported by a tortoise. When his European interlocutor said “But how about the tortoise?” he replied that he was tired of metaphysics and wanted to change the subject.

In 1967 linguist John Robert Ross included an anecdote about William James in his doctoral thesis. Recall, James did use the punchline “rocks all the way down” in 1882, but there is no substantive evidence that he used the punchline “turtles all the way down” as suggested in this tale:22

“And it’s this: The first turtle stands on the back of a second, far larger, turtle, who stands directly under him.”

“But what does this second turtle stand on?” persisted James patiently.

To this, the little old lady crowed triumphantly,

“It’s no use, Mr. James — it’s turtles all the way down.”

In 1979 science communicator Carl Sagan included a version of the story in “Broca’s Brain”:23

Some ancient Asian cosmological views are close to the idea of an infinite regression of causes, as exemplified in the following apocryphal story: A Western traveler encountering an Oriental philosopher asks him to describe the nature of the world:

“It is a great ball resting on the flat back of the world turtle.”

“Ah yes, but what does the world turtle stand on?”

“On the back of a still larger turtle.”

“Yes, but what does he stand on?”

“A very perceptive question. But it’s no use, mister; it’s turtles all the way down.”

In 1983 the prominent English fantasy author Terry Pratchett used a version of this cosmography in “The Colour of Magic”, the first novel in the Discworld series, which has a flat world carried by four elephants standing on an enormous turtle traveling through space:24

Great A’Tuin the turtle comes, swimming slowly through the interstellar gulf, hydrogen frost on his ponderous limbs, his huge and ancient shell pocked with meteor craters.

The turtle’s eyes are fixed on a distant destination while it thinks of the weight it is carrying:

Most of the weight is of course accounted for by Berilia, Tubul, Great T’Phon and Jerakeen, the four giant elephants upon whose broad and star-tanned shoulders the disc of the World rests, garlanded by the long waterfall at its vast circumference and domed by the baby-blue vault of Heaven.

In conclusion, this overview shows that a variety of creatures were included in the stack of animals in cosmographical models. Also, the entity or entities at the bottom of the stack varied. Some animals had infinitely long legs or tails. In 1883 a comical tale referred to an infinite series of rocks. In 1854 a debater referred to an infinite series of tortoises, and in 1886 there was an infinite series of turtles. The tale has been evolving for centuries.

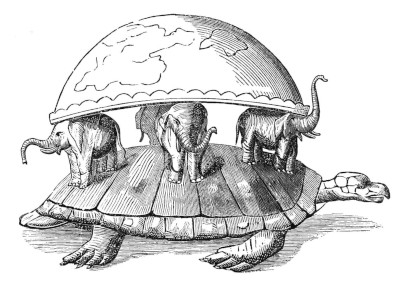

Image Notes: Illustration of the Earth supported by four elephants on top of a tortoise. This public domain illustration appeared in “The Popular Science Monthly” in March 1877.

Acknowledgement: Great thanks to Paul Rauber, Helen De Cruz, Weltgeist redux, Fake History Hunter whose inquiries led QI to formulate this question and perform this exploration. Thanks to the forum participants at “The Straight Dope”. Also, thanks to the volunteer editors at Wikipedia and Wikiquote. In addition, thanks to Michael Scopp, Sir Autumn Mandrake, and ClimateRemind who suggested adding a citation to Terry Pratchett.

Update History: On March 20, 2025 the format of the bibliographical notes was updated.

- 1601, Epistola Patris Nicolai Pimentæ, Visitatoris Societatis IESV in India Orientali, Ad R.P. Claudium Aquauiuam eiusdem Societatis Præpositum Generalem, Goæ viij. Kal. Ianuarij 1599, Section: Exemplum litterarum P. Emmanuelis de Veiga ab urbe regia Chandegrino, 14. Cal. Octobris anno 1599, Start Page 150, Quote Page 154, Apud Aloysium Zannettum, Romae. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1626, Purchas His Pilgrimage, Or Relations of the World and the Religions Obserued in All Ages and Places Author: Samuel Purchas (Parson of St. Martins by Ludgate, London), Fourth Edition, The Fifth Booke, Chapter 11: Of the Kingdome of Narsinga and Bisnagar, Section: III Of many other strange Rites: And of Saint Thomae, Quote Page 561, Printed by William Stansby for Henrie Fetherstone, London. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1690, An Essay Concerning Humane Understanding by John Locke, Book 2 of 4, Chapter 23: Of Our Complex Ideas of Substances, Quote Page 136, Printed by Eliz. Holt for Thomas Basset, London. (Early English Books Online EEBO ProQuest) ↩︎

- 1804, British Synonymy; Or, An Attempt At Regulating the Choice of Words in Familiar Conversation by Hester Lynch Piozzi, Topic: To Wrangle, To Dispute, To Altercate, Quote Page 347, Published by Parsons and Galignani, Paris, France. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1826 May, The Asiatic Journal, Volume 21, Number 125, Budhuism, Start Page 570, Quote Page 571, Printed for Kingsbury, Parbury, & Allen, London. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1836 April 19, Richmond Enquirer, Election of Governor, Quote Page 3, Column 3, Richmond, Virginia. (Newspapers_com) ↩︎

- 1838 August 18, The New-Yorker, Volume 5, Number 22, Unwritten Philosophy, Quote Page 344, Column 2, New York, New York. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1838 September 15,The New-York Mirror, Volume 16, Number 12, Unwritten Philosophy, Quote Page 91, Quote Page 2, New York, New York. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1842, The London University Magazine, Volume 1, Number 2, Corn Law and Customs Act, Start Page 131, Quote Page 136, Fisher, Son, & Company, London. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1844, The Hierarchical Despotism, Lecture 4: Sophisms of the Apostolical Succession by Reverend George B. Cheever, Start Page 1, Quote Page 23, Saxton & Miles, New York. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1845 July, The Yale Literary Magazine, Conducted by the Students of Yale College, Volume 10, Number 8, Criticism a La Mode, Start Page 365, Quote Page 366, Published by A. H. Maltby, New Haven, Connecticut. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1894 (1893 Copyright), Excursions by Henry David Thoreau, Entry date: May 4, 1852, Start Page 427, Quote Page 428, Houghton, Mifflin and Company, Boston, Massachusetts. (Internet Archive at Archive.org) link ↩︎

- 1854, Great Discussion on the Origin, Authority, and Tendency of the Bible, Between Rev. J. F. Berg, D.D., of Philadelphia and Joseph Barker, of Ohio, Discussion on the Bible, Second Evening, Remarks of Rev. Dr. Berg, Start Page 43, Quote Page 47, Printed by George Turner, Stoke-Upon-Trent, England. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1867 October, The North American Review, Volume 105, Key and Oppert on Indo European Philology (by William Dwight Whitney), Start Page 521, Quote Page 544, Ticknor and Fields, Boston, Massachusetts. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1882, The New Version: Lectures by George Chainey, Nothing, Start Page 8, Quote Page 8, Published by George Chainey, Boston, Massachusetts. (HathiTrust Full View) link ↩︎

- 1882 July, The Princeton Review, Rationality, Activity and Faith by Professor William James (Harvard College), Start Page 58, Quote Page 82, New York. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1886 May, Facts: A Monthly Magazine Devoted to Mental and Spiritual Phenomena, Volume 5, Number 5, Mr. W. J. Colville’s Metaphysics by Dr. Dean Clarke, Start Page 127, Quote Page 130, Facts Publishing Company, Boston, Massachusetts. (HathiTrust Full View) link ↩︎

- 1888, Mark Twain’s Library of Humor, Compiled by Mark Twain, Lectures On Astronomy by John Phoenix, Start Page 453, Quote Page 455, Charles L. Webster & Company, New York. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1904, How to Know the Starry Heavens: An Invitation to the Study of Suns and Worlds by Edward Irving, Chapter 1: Apparent Motions of the Heavenly Bodies as Shown by Observation, Quote Page 1 and 2, Frederick A. Stokes Company, New York. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1917 October 29, The Morning Call, Where Would It End?, Quote Page 4, Column 1, Paterson, New Jersey. (Newspapers_com) ↩︎

- 1927, Philosophy by Bertrand Russell, Essay: Causal Laws In Physics, Start Page 114, Quote Page 120 and 121, W. W. Norton & Company, New York. (Verified with scans) ↩︎

- 1967 September, Constraints on Variables in Syntax by John Robert Ross, Doctoral Dissertation at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Quote Page iv and v, Cambridge, Massachusetts. (Accessed August 19, 2021 via internet Archive at archive.org) ↩︎

- 1979, Broca’s Brain: Reflections on the Romance of Science by Carl Sagan, Chapter 24: Gott and the Turtles, Start Page 292, Quote Page 292 and 293, Random House, New York. (Verified with scans) ↩︎

- 1983, The Colour of Magic by Terry Pratchett, Chapter: Prologue, Quote Page 1, St. Martin’s Press, New York. (Verified with scans) ↩︎