George Bernard Shaw? William Butler Yeats? Anonymous? H. W. Garrod? Lord Dunsany? Lytton Strachey?

Question for Quote Investigator: While the First World War was raging an unhappy woman approached a famous British scholar and poet and rebuked him for not enlisting. She stated emphatically that young men were fighting and dying to defend civilization. Here are two versions of sage’s response:

1) But Madam, I am the civilization for which they are fighting.

2) Are you aware, Madam, that I am the civilization for which they are dying?

In the version of the tale I was told the riposte was delivered by the Oxford classical scholar H. W. Garrod. But other possibilities have been mentioned, e.g., Lytton Strachey and Bernard Shaw. Would you please explore this anecdote?

Reply from Quote Investigator: The earliest instance of this story located by QI was published in August 1914 in a London periodical called “The New Age: A Weekly Review of Politics, Literature and Art”. The disparager was a soldier, and the respondent was an unnamed artist. The passage below employed the British variant spelling for “civilisation” with an “s” instead of a “z”. Boldface has been added to excerpts:1

I heard another good retort of an artist upon a volunteer who reproached him for not enlisting. I, he said, am the civilisation you are fighting for.

Here are additional selected citations in chronological order.

In October 1914 a closely matching story was printed in newspapers in Perth, Australia2 and Ashburton, New Zealand;3 both papers acknowledged “The New Age”:

“I heard a good retort of an artist upon a volunteer who reproached him for not enlisting,” says a writer in the “New Age.” “I,” he said, “am the civilisation you are fighting for.”

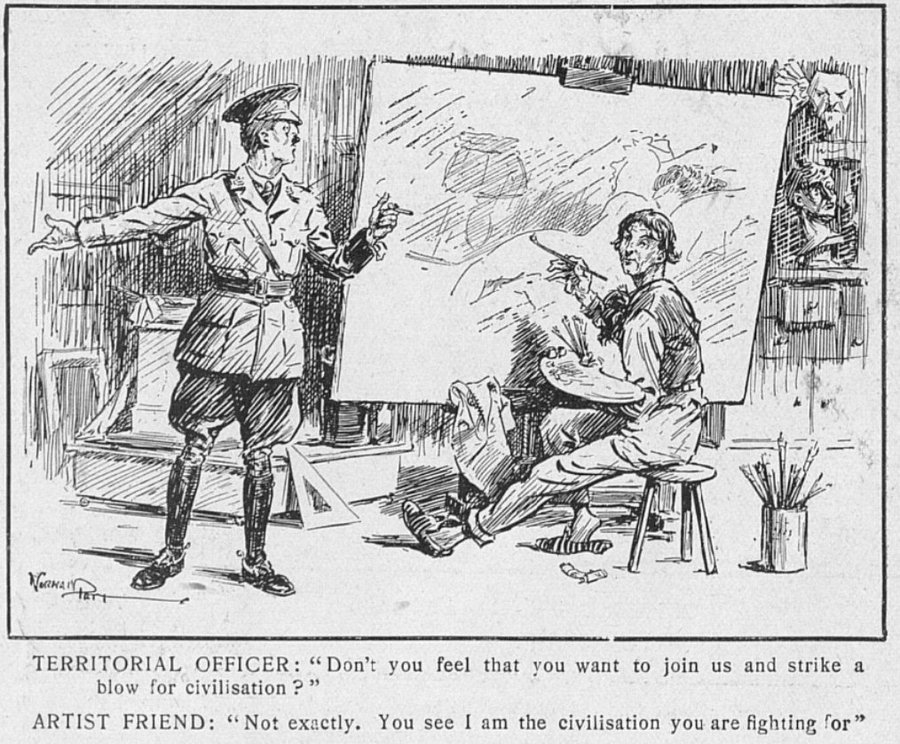

In February 1915 “The Bystander” magazine of London published a cartoon with the following caption. See the image at the top of this article:4

TERRITORIAL OFFICER : “Don’t you feel that you want to join us and strike a blow for civilisation?”

ARTIST FRIEND: “Not exactly. You see I am the civilisation you are fighting for”

By April 1915 the anecdote was being disseminated in the United States. For example, “The Youth’s Companion” of Boston, Massachusetts printed the following item under the title “I Am It”. This instance employed the phrase “that civilization” instead of “the civilisation”:5

The New Age tells of an artist of some reputation who was reproached by a volunteer for not enlisting. He gazed a while at the younger man with impenetrable calm; then, slowly and with grave dignity, he said: “I am that civilization you are fighting for.”

In the following months instances were printed in the humor magazine “Life” of New York,6 “The Washington Post” of Washington, D.C.,7 “The Salt Lake Tribune” of Salt Lake City, Utah,8 and other periodicals.

In November 1919 a staff writer for the “St. Louis Post-Dispatch” of St. Louis, Missouri published a different version of the tale. The artist was identified as the prominent Irish fantasy writer Lord Dunsany, and he was approached by two women instead of a soldier:9

Lord Dunsany, who is to be in St. Louis next week, was one day sitting in a London cafe. Two young women drumming up recruits for the British army came in. They knew his lordship and hastened over to him.

“Aren’t you going to fight for civilization, Lord Dunsany?” one of them asked.

There is no droller person on earth today than this same Lord Dunsany.

“My dear young woman,” he said, looking up from his tea, “I am the civilization for which we are fighting.”

The anecdote above was unlikely to be true because Lord Dunsany did serve in the military during the Boer War as a Second Lieutenant and during World War I as a Captain. Perhaps the upcoming visit of Dunsany to St. Louis inspired some creative storytelling. A week later the tale above was printed in “The Washington Post” with an acknowledgement to the “St. Louis Post-Dispatch”.10

In 1937 Douglas Jerrold published an autobiography titled “Georgian Adventure”, and he included a colorful instance of the tale. Jerrold stated that the military service question was aimed at the scholar H. W. Garrod.11 In 1940 “The Ottawa Journal” newspaper of Canada reprinted the anecdote and credited Jerrold’s book:12

When H. W. Garrod, Professor of Poetry at Oxford University, was offered a white flag by an enthusiastic woman in 1916—during the first World War—with the remark, “Sir, are you aware that in Flanders young men are dying for civilization?” he replied with a bow—says Douglas Jerrold (in “Georgian Adventure”):

“Are you aware, Madam, that I am the civilization for which they are dying?”

In May 1940 a gossip columnist recounted a version of the story from the comedian Henry (Henny) Youngman that featured the famous playwright George Bernard Shaw. At the outbreak of WWI Shaw would have been 58 years old; he strongly opposed the war:13

Henny Youngman was one of a group discussing the current international situation at Colbert’s the other dinner-time, and he recalled the heartless, characteristic quip attributed to George Bernard Shaw during the first World War.

Some heckling acquaintances in London asked the playwright why he was not at the front fighting to save civilization.

“I,” replied Shaw, “am the civilization they are trying to save!”

In April 1941 “The Christian Science Monitor” printed an article with a London dateline that included an interesting version of the tale:14

A professor of poetry was stopped in the street by an irate woman during the last war. She demanded, “Why aren’t you with our soldiers fighting to preserve civilization?” He replied, “Madam, I am the civilization they are fighting to preserve.” The professor had been five times rejected for military service, and so could give that reply with an easy conscience. Yet there is more than a suspicion of truth in it. It is folly to abandon culture when culture is one of the things that make civilization worthwhile.

In 1953 a book reviewer in the London journal “The Twentieth Century” skeptically ascribed the rejoinder to the well-known Irish poet W. B. Yeats:15

Being ‘still civilized’ is now a kind of profession. ‘I am the civilization that you are defending,’ W. B. Yeats is supposed to have said to a soldier during the First World War. It is difficult to believe that Yeats ever made such a remark…

In 1972 “The Times” of London printed an article by Bernard Levin about the ten year run of the influential literary magazine “Horizon”. Levin included an instance of the anecdote featuring the British writer Lytton Strachey:16

I think it was Lytton Strachey who, badgered during the First World War by a crone bearing white feathers who demanded to know why he was not fighting to preserve civilization, replied: “Madam, I am the civilization that they are fighting to preserve.”

BBC Radio personality and top quotation expert Nigel Rees discussed the remark in the 2006 reference “Brewer’s Famous Quotations”17 and in “The Quote Unquote Newsletter” of 2013.18 Rees noted that an instance was contained in Hugh MacDiarmid’s 1935 poem “At the Cenotaph”. In addition, a version of the anecdote with Garrod appeared in the 1970 book “Oxford Now and Then”.19 QI was inspired to research this topic by the pioneering efforts of Rees.

In conclusion, the earliest examples of this anecdote in 1914 did not identify the participants. An unnamed soldier criticized an unnamed artist. The story evolved over time, and the faultfinder was transformed into a woman. Several prominent individuals were implausibly substituted into the tale. QI suspects that the tale was apocryphal. Yet, it was conceivable that W. H. Garrod did deliver the rejoinder, and the earliest instances of the anecdote garbled the details.

Image Notes: February 17, 1915 cartoon from “The Bystander” of London.

Acknowledgement: Great thanks to Nigel Rees whose previous investigation led QI to formulate this question and perform this exploration. Thanks also to the discussant Dan Nussbaum. Further thanks to Simon Koppel, Theo Nash, Mary Beard, and others who participated in a twitter thread that covered this topic. One participant located the 1915 cartoon in “The Bystander”.

Update History: On November 22, 2015 the 1938 citation for “Georgian Adventure” was verified on paper and added to the article. On May 14, 2023 the 1915 cartoon from “The Bystander” was added to the article. On January 15, 2025 the format of the bibliographical notes was updated.

- 1914 August 20, “The New Age: A Weekly Review of Politics, Literature and Art”, Volume 15, Observations and Reflections by A.B.C., (short filler-type item), Quote Page 379, Column 1, Published by New Age Press, Limited, London. (Verified with page images from brown.edu) ↩︎

- 1914 October 24, The West Australian, Table Talk: From Far and Near, Quote Page 11, Column 1, Perth, Western Australia. (Trove Digitized newspapers) ↩︎

- 1914 October 17, Ashburton Guardian, Volume 33, Here and There, Quote Page 6, Column 1, Ashburton, New Zealand. (Papers Past: National Library of New Zealand) ↩︎

- 1915 February 17, The Bystander, Volume 45, Number 585, (Single panel cartoon), Quote Page 220, H. R. Baines & Company, London, England. (Google Books Full View) link ↩︎

- 1915 April 22, The Youth’s Companion, Volume 89, I Am It, (Short freestanding item with acknowledgement to The New Age), Quote Page 204, Column 4, Perry Mason, Boston, Massachusetts. (ProQuest American Periodicals) ↩︎

- 1915 May 20, Life, I Am It, (Short freestanding item with acknowledgement to The New Age), Quote Page 920, Column 1, Life Publishing Company, New York. (ProQuest American Periodicals) ↩︎

- 1915 June 22, Washington Post, I Am It, (Short freestanding item with acknowledgement to New Age), Quote Page 6, Column 4, Washington, D.C. (ProQuest) ↩︎

- 1916 April 9, Salt Lake Tribune, I Am It, (Short freestanding item with acknowledgement to The New Age), Quote Page 8, Column 7, Salt Lake City, Utah. (NewspaperArchive) ↩︎

- 1919 November 8, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Just a Minute by Clark McAdams (Written for the Post-Dispatch), Quote Page 12, Column 5, St. Louis, Missouri. (ProQuest) ↩︎

- 1919 November 16, Washington Post, Section: Sunday Magazine, He Said It, Quote Page SM12, Column 2, Washington, D.C. (ProQuest) ↩︎

- 1938, Georgian Adventure: The Autobiography of Douglas Jerrold, Chapter 8: Post War, Quote Page 242, (First Published in 1937 by William Collins Sons, London), Special Edition for The “Right” Book Club, Soho Square, London. (Verified on paper in 1938 special edition) ↩︎

- 1940 October 12, The Ottawa Journal, An Attic Salt-Shaker by W. Orton Tewson, Quote Page 21, Column 7, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. (Newspapers_com) ↩︎

- 1940 May 3, Trenton Evening Times, The Voice of Broadway by Dorothy Kilgallen, Quote Page 14, Column 3, Trenton, New Jersey. (GenealogyBank) ↩︎

- 1941 April 19, Christian Science Monitor, ‘No Time for Comedy’ in London by Harold Hobson (Dateline London), Quote Page 13, Column 2, Boston, Massachusetts. (ProQuest) ↩︎

- 1953 July, The Twentieth Century, Volume 154, (Review of “Love Among the Ruins by Evelyn Waugh; unidentified reviewer; initials of next review writer are J.G.W.), Quote Page 79, The Nineteenth Century and After Limited, London. (Verified on paper) ↩︎

- 1972 August 31, The Times, My Horizons of gold by Bernard Levin, Quote Page 12, Column 8, London, England. (The Times database; Gale Group) ↩︎

- 2006, Brewer’s Famous Quotations, Edited by Nigel Rees, Section Heathcote William Garrod, Quote Page 209, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London. (Verified on paper) ↩︎

- 2013 April, The Quote Unquote Newsletter, Volume 22, Number 2, Edited by Nigel Rees, Quoter’s Digest, Quote Page 6 and 7, Published and distributed by Nigel Rees, Hillgate Place, London, Website: www.quote-unquote.org.uk link ↩︎

- 2013 July, The Quote Unquote Newsletter, Volume 22, Number 3, Edited by Nigel Rees, Garrod’s Civilization, Quote Page 5, Published and distributed by Nigel Rees, Hillgate Place, London, Website: www.quote-unquote.org.uk link ↩︎