Bill Gates? Frank Gilbreth Sr., Clarence Bleicher? Walter Chrysler? Apocryphal? Anonymous?

Question for Quote Investigator: There is a quotation offering eccentric advice that is often attributed to the billionaire software magnate Bill Gates:

I will always choose a lazy person to do a difficult (or hard) job because a lazy person will find an easy way to do it.

However, a very similar comment has been ascribed to Walter Chrysler who was famous for starting the Chrysler car company:

Whenever there is a hard job to be done I assign it to a lazy man; he is sure to find an easy way of doing it.

Are these really the words of Gates or Chrysler?

Reply from Quote Investigator: Probably not. QI has located no substantive support for the claim that Bill Gates or Walter Chrysler made this remark.

The earliest evidence known to QI championing the counter-intuitive adroitness of the lazy man appeared in an article published in “Popular Science Monthly” in 1920. Frank B. Gilbreth Sr. evaluated the motions of workmen to determine the most efficient techniques to perform tasks:1

Gilbreth studied the methods of various bricklayers—the poor workmen and the best ones, and he stumbled upon an astonishing fact of great importance and significance. He found that he could learn most from the lazy man!

Most of the chance improvements in human motions that eliminate unnecessary movement and reduce fatigue have been hit upon, Gilbreth thinks, by men who were lazy—so lazy that every needless step counted.”

Another important thing Gilbreth noted was that the so-called expert factory workers are often the most wasteful of their motions and strength. Because of their energy and ability to work at high speed, such men may be able to produce a large quantity of good work, and thus qualify as experts, but they tire themselves out of all proportion to the amount of work done.

The above valuable citation was located by librarian Erica Cathers who shared it with QI.

Gilbreth’s ideas were influential, and his comments about the “lazy man” probably reached the ears of many managers in industry. In 1947 an automobile executive named Clarence Bleicher testified before a U.S. Senate committee. He was the president of a division of Chrysler Corporation that built DeSoto automobiles. QI hypothesizes that Bleicher’s remarks were refashioned over time to yield the modern quotations. The following excerpt includes a question that was posed by Allen J. Ellender who was a Senator from Louisiana:2

Mr. BLEICHER. …So if you have got a job that is tough—I have taught my foremen this for some months now—if you get a tough job, one that is hard, and you haven’t got a way to make it easy, put a lazy man on it, and after 10 days he will have an easy way to do it, and you perfect that way and you will have it in pretty good shape. [Laughter.]…

Senator ELLENDER. You say you would put a lazy man on a job to find an easy way to do it. Why would you say a lazy man rather than a hard worker?

Mr. BLEICHER. Because the lazy man will find an easy way to do it. He may not do much, but he will find an easy way to do it. [Laughter.]

Senator ELLENDER. That has been your experience?

Mr. BLEICHER. That has been my experience.

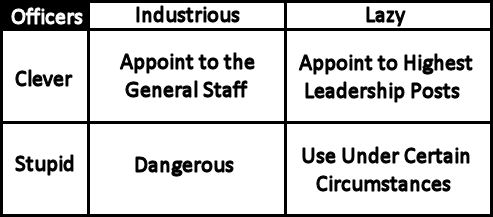

A thematically related viewpoint was expressed by German General Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord in the 1930s. However, Hammerstein was discussing the selection of military officers, and he assigned the greatest value to individuals who were both lazy and smart. The quotation under examination here does not mention intelligence. The QI entry on the Hammerstein quotation is available here.

Here are additional selected citations in chronological order.

Continue reading “Quote Origin: Choose a Lazy Person To Do a Hard Job Because That Person Will Find an Easy Way To Do It”